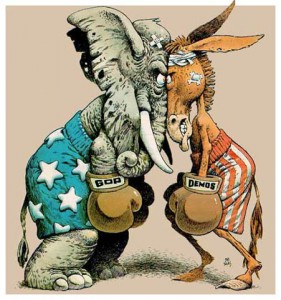

We live in a world that is fragmented by special interest groups represented by social classes, political parties, religious sects, race, education, gender, age, income, even language. Divisions between groups and factions range from subtle to severe, almost to the point of convulsive, as in cases involving fundamentalist religious zeal, separating fanatics from everyone else, even to the point of genocide and other heinous crimes that under any other circumstances would be considered unspeakable acts of horror, even by the zealots themselves.

We live in a world that is fragmented by special interest groups represented by social classes, political parties, religious sects, race, education, gender, age, income, even language. Divisions between groups and factions range from subtle to severe, almost to the point of convulsive, as in cases involving fundamentalist religious zeal, separating fanatics from everyone else, even to the point of genocide and other heinous crimes that under any other circumstances would be considered unspeakable acts of horror, even by the zealots themselves.

As human beings we share a need to belong. Being excluded from groups with which we identify in some way makes us feel separate in negative ways, and our sense of self-worth takes a nosedive from the awful feeling of being left out.

As human beings we share a need to belong. Being excluded from groups with which we identify in some way makes us feel separate in negative ways, and our sense of self-worth takes a nosedive from the awful feeling of being left out.

At this time of year, for example, group loyalty to sports teams becomes laser sharp regarding the Olympics and football teams for the Super Bowl. That powerful feeling of being outside the borders of acceptance is especially vigorous on a larger scale at a time when the division between the haves and the have-nots (the one percent versus everybody else) is so pronounced. No matter who we are, we are all strangers somewhere in places we feel we don’t belong. The borders we create are often purely artificial, or at least more psychological than physical. Our human tendency to categorize is also what prevents us from seeing our species as one vast but varied human family.

At this time of year, for example, group loyalty to sports teams becomes laser sharp regarding the Olympics and football teams for the Super Bowl. That powerful feeling of being outside the borders of acceptance is especially vigorous on a larger scale at a time when the division between the haves and the have-nots (the one percent versus everybody else) is so pronounced. No matter who we are, we are all strangers somewhere in places we feel we don’t belong. The borders we create are often purely artificial, or at least more psychological than physical. Our human tendency to categorize is also what prevents us from seeing our species as one vast but varied human family.

Our insatiable need to create comfort zones socially, economically, politically, and religiously creates at times much more strife than harmony. Such divisions are based also upon our all too human need or desire to be “right,” which generally means that somebody has to be “wrong” too.

Our insatiable need to create comfort zones socially, economically, politically, and religiously creates at times much more strife than harmony. Such divisions are based also upon our all too human need or desire to be “right,” which generally means that somebody has to be “wrong” too.

Even the best informed among us live within walls of some kind of prejudice, especially when we accept without question what has been told to us by those who came before. Ignorance breeds ignorance until we see that as human beings, we are probably more alike than we ever suspected. There was a time when slavery was considered by many to be perfectly all right and was condoned even from pulpits all across our country. It seems we can justify almost anything, at least for a while.

Even the best informed among us live within walls of some kind of prejudice, especially when we accept without question what has been told to us by those who came before. Ignorance breeds ignorance until we see that as human beings, we are probably more alike than we ever suspected. There was a time when slavery was considered by many to be perfectly all right and was condoned even from pulpits all across our country. It seems we can justify almost anything, at least for a while.

It would be a much more harmonious world if we could remember that everyone has a life story to tell and that all those stories contain elements of pain and joy, despair and hope, ignorance and awareness, fear and courage that, in their purest forms, have not changed so very much over many thousands of years, any more than the human face itself has changed in that time.

It would be a much more harmonious world if we could remember that everyone has a life story to tell and that all those stories contain elements of pain and joy, despair and hope, ignorance and awareness, fear and courage that, in their purest forms, have not changed so very much over many thousands of years, any more than the human face itself has changed in that time.

Our human tendency to look down our noses at others who are different in some ways is perhaps one of the greatest stumbling blocks impeding enlightenment, and it is a stumbling block that cannot really be removed by technology alone. In that sense, we have a long way to go before we reach any mountain top or promise land. JB

Our human tendency to look down our noses at others who are different in some ways is perhaps one of the greatest stumbling blocks impeding enlightenment, and it is a stumbling block that cannot really be removed by technology alone. In that sense, we have a long way to go before we reach any mountain top or promise land. JB