The next day during homeroom I began collecting book rental and was surprised at how many students brought cash instead of checks. My brain became a festival of arithmetic through adding and subtracting for that big, brown envelope. That was a time before pocket calculators were less than $189, and book rental collection with its record keeping responsibility was just one more job placed upon the already tired shoulders of teaching staff. It was recommended that we turn in to the main office each afternoon any book money turned in that day. We as teachers were responsible for the money. Like the other new teachers, fresh out of college and flat broke, I didn’t always turn in the cash after school, just the checks, keeping a personal record of what I had borrowed and would be putting back into the envelope before the deadline, which would come after our first payday in two weeks. I used the money, not for any frivolous purpose, but for things like lunch, gas for my ride to and from work, toothpaste, shaving cream, and a haircut. None of this did much for my ego, but I blamed necessity (which would ever hold up in a courtroom) on my stealthy behavior.

It seemed that most of my freshmen had read the short story, “The Piece of String” I had given as homework the day before. After a brief written quiz over the story, I posed questions to engage the class in a discussion on the story’s purpose and meaning. The theme is the damage an ugly rumor can cause, even over a period of many years. Though the setting of the story is a rural, 19th Century French village, the circumstances carried over to school life, which is a kind of community too. The conflict in which the main character finds himself registered with students already familiar with the cruel and lasting dangers of even petty rumors (something many teens live for). In the story a man’s life is destroyed by such a rumor that grows over time. The reader’s sympathy is with the main character, Maitre Hauchecome, who rightfully defends his innocence to no avail for years over false accusations based upon faulty interpretation instead of hard evidence. The lack of trust among townspeople, who are willing, even anxious to believe the worst, creates an atmosphere of suspicion that makes the village an awful place for everyone to live.

It seemed that most of my freshmen had read the short story, “The Piece of String” I had given as homework the day before. After a brief written quiz over the story, I posed questions to engage the class in a discussion on the story’s purpose and meaning. The theme is the damage an ugly rumor can cause, even over a period of many years. Though the setting of the story is a rural, 19th Century French village, the circumstances carried over to school life, which is a kind of community too. The conflict in which the main character finds himself registered with students already familiar with the cruel and lasting dangers of even petty rumors (something many teens live for). In the story a man’s life is destroyed by such a rumor that grows over time. The reader’s sympathy is with the main character, Maitre Hauchecome, who rightfully defends his innocence to no avail for years over false accusations based upon faulty interpretation instead of hard evidence. The lack of trust among townspeople, who are willing, even anxious to believe the worst, creates an atmosphere of suspicion that makes the village an awful place for everyone to live.

The class identified parallels between life in that little village and life as a student in a school setting. In their comments, students used words like, fairness, justice, lies, judging, proof, and meanness. I was so proud of the way they approached the theme, identified it, and then related the conflicts to their own experiences. All three classes did this, making me feel like doing cartwheels in the hallway after each session.

The class identified parallels between life in that little village and life as a student in a school setting. In their comments, students used words like, fairness, justice, lies, judging, proof, and meanness. I was so proud of the way they approached the theme, identified it, and then related the conflicts to their own experiences. All three classes did this, making me feel like doing cartwheels in the hallway after each session.

A minor issue occurred in third period, when one boy, Sam, raised his hand to say that in his book there was a different author listed for that story. When I asked who was in his book (thinking there might actually have been some sort of misprint), he answered, “Guy something or other,” his pronunciation of the first name being with a hard “g” followed by a long “i” as in “guy and gal.” When I pronounced it the French way (hard “g” followed by a long “e”), he looked more confused. When I continued, he raised his hand again to say, “It says Guy in my book.” His pronunciation hadn’t changed at all. When I explained again the French pronunciation, he raised his hand yet again with the most puzzled facial expression and asked, “Are you SURE?” That was when something in my brain snapped, and I indulged in some perfectly shameless sarcasm by saying, “OK, Sammy. You got me. I made the whole thing up just to put one over on you. You may pronounce Monsieur de Maupassant’s first name in whatever way makes you happy. My only request is that you spell it correctly.” It appeared by the look on his face that even my sarcasm had just flown right over his head, but it didn’t matter. I felt better.

A minor issue occurred in third period, when one boy, Sam, raised his hand to say that in his book there was a different author listed for that story. When I asked who was in his book (thinking there might actually have been some sort of misprint), he answered, “Guy something or other,” his pronunciation of the first name being with a hard “g” followed by a long “i” as in “guy and gal.” When I pronounced it the French way (hard “g” followed by a long “e”), he looked more confused. When I continued, he raised his hand again to say, “It says Guy in my book.” His pronunciation hadn’t changed at all. When I explained again the French pronunciation, he raised his hand yet again with the most puzzled facial expression and asked, “Are you SURE?” That was when something in my brain snapped, and I indulged in some perfectly shameless sarcasm by saying, “OK, Sammy. You got me. I made the whole thing up just to put one over on you. You may pronounce Monsieur de Maupassant’s first name in whatever way makes you happy. My only request is that you spell it correctly.” It appeared by the look on his face that even my sarcasm had just flown right over his head, but it didn’t matter. I felt better.

The only real downer in all three freshman classes was once again with Johnny in sixth period, who continued to depend upon his response of “I dunno” to any and every question, his dark and full head of hair covering his eyes, as though he didn’t want to see or be seen. As he shuffled out of the room at the end of class that day, I realized it might be time for me to contact his parents, but I decided to wait a few more days before making the phone call, so that he wouldn’t see me as a narc. It was Debbie standing before my desk after class, who was my next challenge.

We had only five minutes before Debbie would have to be in her seventh period biology class, so I tried to distill my comments on plagiarism into the gentlest but clearest message. I told Debbie that the poem was superb, and I congratulated her on her excellent taste. Then I added that Elizabeth Barrett Browning would not appreciate the unauthorized claim of its creation by a freshman girl over a century later. Debbie seemed surprised that “Sonnets from the Portuguese” had been written to Robert Browning and was one of the most famous collections of poems in the English language.

We had only five minutes before Debbie would have to be in her seventh period biology class, so I tried to distill my comments on plagiarism into the gentlest but clearest message. I told Debbie that the poem was superb, and I congratulated her on her excellent taste. Then I added that Elizabeth Barrett Browning would not appreciate the unauthorized claim of its creation by a freshman girl over a century later. Debbie seemed surprised that “Sonnets from the Portuguese” had been written to Robert Browning and was one of the most famous collections of poems in the English language.

Debbie’s defense was that she had been inspired by the sonnet but that what she had given me was not really Mrs. Browning’s. When I asked for some clarification, Debbie replied that in the fourth line of the Browning poem, the words, “being” and “grace” were capitalized, but that in Debbie’s “own poem,” they were not. Though shocked by her feeble attempt at being acquitted of blatant theft, I was not exactly speechless. I explained it in terms of stealing, which in many cases would have legal consequences. I paused for just a moment as I looked over at the big brown envelope for book rental still on my desk and then continued.

Debbie’s defense was that she had been inspired by the sonnet but that what she had given me was not really Mrs. Browning’s. When I asked for some clarification, Debbie replied that in the fourth line of the Browning poem, the words, “being” and “grace” were capitalized, but that in Debbie’s “own poem,” they were not. Though shocked by her feeble attempt at being acquitted of blatant theft, I was not exactly speechless. I explained it in terms of stealing, which in many cases would have legal consequences. I paused for just a moment as I looked over at the big brown envelope for book rental still on my desk and then continued.

As I had already gone overtime in my comments, I wrote Debbie a pass to her seventh period while ending my mini-lecture in saying that I was much more interested in reading Debbie’s own work, whatever that might be, and that in future I would be very happy to read anything she gave me, as long as she had created it by herself. I told her it was all about creativity and honesty. She then left my classroom, apparently unscathed by anything I had said, and I wondered if the next poem she handed in might be “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” At least she stole only from the best.

As I had already gone overtime in my comments, I wrote Debbie a pass to her seventh period while ending my mini-lecture in saying that I was much more interested in reading Debbie’s own work, whatever that might be, and that in future I would be very happy to read anything she gave me, as long as she had created it by herself. I told her it was all about creativity and honesty. She then left my classroom, apparently unscathed by anything I had said, and I wondered if the next poem she handed in might be “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” At least she stole only from the best.

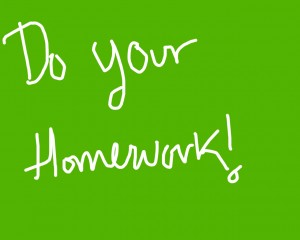

During conference period that day I graded the quizzes over “The Piece of String” and was generally pleased that most of the students had read the assignment, but when I got to the papers for period six, I was astonished by Johnny’s paper, which showed his name, the date, and English I written neatly where they were supposed to be, in the upper right-hand corner. For all ten answers, however, he had written, “I don’t know,” something I would certainly have deduced, had he not bothered to write it. The real shock, though, came when I turned the paper over to see a drawing of me. Not only was it labeled, “Mr. Bolinger,” but it actually looked like me, I mean REALLY like me, except that in the drawing my right arm was in a sling, there were stitches along my forehead, and I was on crutches. Also there was a cartoon bubble from my mouth that said, “Do your homework!” It was obvious by the skill of the drawing itself that the problem I had seen before involved a much more complex and talented young man than I had imagined. It was time for me to do something before things got worse.

During conference period that day I graded the quizzes over “The Piece of String” and was generally pleased that most of the students had read the assignment, but when I got to the papers for period six, I was astonished by Johnny’s paper, which showed his name, the date, and English I written neatly where they were supposed to be, in the upper right-hand corner. For all ten answers, however, he had written, “I don’t know,” something I would certainly have deduced, had he not bothered to write it. The real shock, though, came when I turned the paper over to see a drawing of me. Not only was it labeled, “Mr. Bolinger,” but it actually looked like me, I mean REALLY like me, except that in the drawing my right arm was in a sling, there were stitches along my forehead, and I was on crutches. Also there was a cartoon bubble from my mouth that said, “Do your homework!” It was obvious by the skill of the drawing itself that the problem I had seen before involved a much more complex and talented young man than I had imagined. It was time for me to do something before things got worse.

Because it was only 2:40, I decided to phone Johnny’s parents to see if they could be my allies in helping Johnny find a different purpose for being in my class. I had as yet never heard him say anything but, “I dunno” in the most muffled voice. I felt terrible that I had somehow got off on the wrong foot with him, or he with me, but I thought things could be set right if his parents could help by encouraging him to do his work and shoot for a diploma instead of a protective order from the police.

From the school enrollment card I got Johnny’s phone number and placed the call in the English Department office. I waited for five rings before someone picked up the receiver but saying nothing. I heard breathing, so I spoke first. “Hello. May I please speak to Mrs. Madison?”

“Uh huh,” came the response.

“This is Mr. Bolinger at Morton High School, Mrs. Madison, and I’m calling about your son Johnny, who’s in my sixth period English I class, where he seems to be having some kind of struggle doing his work. You know him best, so I’m hoping that as a team you and I can talk with him so he can get on the right track to getting a credit for the semester.”

There was an uncomfortable silence.

There was an uncomfortable silence.

“Hello. Mrs. Madison? Are you still there?”

“Uh huh,” she repeated.

“Well, can you help me get Johnny working on getting that credit?”

“I dunno,” she said before hanging up.

At that moment I had a vision of the Madisons’ family life at home, complete with grunting relatives wearing bear skins and throwing table scraps to a pack of wild dogs roaming through their dining room food pit. I knew in any case that the problem might just be genetic and that I had a battle of epic proportions ahead of me.

My book COME SEPTEMBER, Journey of a High School Teacher is available on Amazon.com as a paperback and Kindle. All my books are also sold at Barnes & Noble. JB