This is a chapter that was originally intended for my first book, ALL MY LAZY RIVERS, an Indiana Childhood, but I’m sharing it as a recollection of kindergarten.

MR. TOOTH DECAY

Most of our first memories of school are from kindergarten, that sensory feast of library paste, crayons, finger paints, monkey bars, maracas, percussion triangles, butter cookies and milk. It is likely the place where we were introduced to formal learning presented to us by paid teachers and staff. For me it was in what at the time seemed a very large and sunny room on the first floor of Harding Elementary School in Hammond, Indiana.

The year was 1951, and I was five years old. Kindergarten was half a day, and I was in the morning shift, so that I was able to be home for lunch and to watch on WGN television the Uncle Johnny Kuhns Show at noon each week day, a lunch which my mother always made sure matched whatever Uncle Johnny was having. It became a tradition that lasted until first grade, when I began having my lunch in the school cafeteria.

My first recollection of school is of lanky Miss Fowler, our kindergarten teacher, sitting at the piano like a praying mantis perched on a flower stem, playing songs like ” Pickin’ Up Paw Paws In the Paw Paw Patch,” and ” Eatin’ Goober Peas,” along with standard school music such as ” America” and ” The Star Spangled Banner.” The piano was a blond Hamilton upright that was never quite in tune. Add to that sound our voices, always enthusiastic but musically askew, and you have one of the primary sounds of Harding in those days. The sounds of locker doors banging, children on their different recess shifts on the playground yelling, singing rhymes to jump rope, scuffles near the teeter-totters and an occasional whistle blowing above it all wove a tapestry of sounds that resonates even now as I think back to those innocent days. I also remember the day that Mary Lou was sitting on the blond wood piano bench plunking out some notes when she actually wet her pants. I was the only one who saw her get off the bench, arranging carefully her blue gingham skirt, leaving a shiny puddle that could be seen only by the reflection from the windows. Later on Miss Fowler sat on the bench for music time and played the most monstrously atonal chord I have ever heard.

Mary Lou was never discovered as the culprit, but the back of Miss Fowler’s dress kept a large stain the rest of that morning. We ended up not singing at all that day.

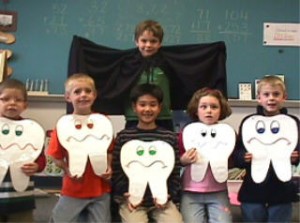

One of our favorite activities was listening to Miss Fowler read us stories from the over-sized books on the classroom shelves. Her voice was filled with cadence and little surprises as she shifted from one character to another. It was impossible not to be riveted by these readings as we sat in a semi-circle on the floor in front of Miss Fowler’s chair, a floor inlaid with large faces of characters from Walt Disney, like Pinocchio, Cinderella and Mickey Mouse. One day Miss Fowler read to us a story about dental hygiene, something that could be tolerated only by five-year-olds. The protagonist was a shiny white tooth named Tommy in what now seems rather an erotic relationship with a big tooth brush named Bruno. Bruno kept Tommy clean and bright with toothpaste and regular polishing in motions that went “up and down and all around.” Miss Fowler demonstrated the motions as all our heads followed her hand in the air. “Up and down, and all around.” We were mesmerized until the shock of seeing the villain enter the story. Mr. Tooth Decay was a sinister, black-caped sneak who came at night when Tommy had not been brushed. This made me wonder if Bruno was out on the town doing some other teeth and neglecting his duty, but Miss Fowler’s voice changed to a menacing baritone when she showed a picture of Tommy on the next page, part of his “face” blackened by decay in a look of utter despair.

In that circle of kids on the floor was Kenneth Kerstal, a boy who always looked angry, because he had only one eyebrow that stretched all the way over his nose with no division there that one finds on most faces. His dark hairy brow was arranged into a permanent sneer that sent the strong message not to mess with him. Sitting there with his hands folded, Ken reacted to the picture of Mr. Tooth Decay with a word that shocked Miss Fowler more than it did us, as she seemed to know what it meant. “The dirty B… ( seven-letter expletive deleted)!” It was the conviction with which Ken said it that impressed me so deeply. We all knew it was not something good to say and also knew that the word “dirty” probably was not even necessary to drive home Kenneth’s point, especially when Miss Fowler took Ken by the hand immediately into the corridor, where we could hear the sound of her hand spanking the back of his corduroy pants. When they came back into the room we couldn’t discern any difference in Ken’s appearance, as he wore that perpetual scowl anyway. He had older brothers who had nurtured his vocabulary even by that tender age, words printed in chalk on the blacktop, winning him and his older siblings regular if not honorable seats in the main office with the principal, Miss McGlaghlan.

Years later, when I was in the fourth grade and Kenneth had the beginnings of an actual beard (and not because it took me longer to get to the fourth grade), my family was taking a drive after church to the Highland Custard Shop. My brother David and I were always given coloring books and crayons in the car to keep us distracted from killing each other. David always finished coloring his pictures first, as he did not mind at all going outside the lines as long as he used all of the crayons in the box. He was Jackson Pollock trapped in the body of a first-grader. At any rate, David became instantly bored after completing the final picture in his coloring book. Demanding that I tear out one of mine for him, he began pulling at a corner of my book. Tugging in the opposite direction, I made him only more determined to get what he wanted until the page was torn from the book. His smug smile triggered something deep in the recesses of my fourth grade brain, something going back to kindergarten and to Kenneth Kerstal. Like the primal scream, the words came out of my mouth at full volume. “Give me that, you dirty b…!”

The car stopped so suddenly and with such a screech, that Mother was practically in the glove compartment. I saw in the rear-view mirror my father’s steely eyes narrowed to laser intensity before his right arm reached back to lift me up by the shirt collar like a hand puppet directly to his angry face. “What did you say, young man?” he inquired.

“Dirty b…?” came my meek reply.

“Dirty b…?” came my meek reply.

“That’s what I thought you said, and if I ever hear you say it again, I’ll stop the car and throw you out onto the street where you can fend for yourself, Mr. Tough Guy!”

Nothing more was said as we drove home. Every bump, every dog barking, every car whizzing by, every horn honking served only to underscore the silence inside our Nash Rambler, until Mother turned on the radio where we heard trombones playing a song called “No Other Love.”

After that I was too afraid to go to my father with the question, “Say, Dad. What exactly IS a dirty b…?” The sudden anger I had witnessed in the car made me think he might throw me into the garbage disposal the next time the words were uttered. The dictionary was no real help, and I did not understand the meaning until seventh or eighth grade, when Kenneth Kerstal gave me the definition in the clearest street language. He would in later years be the source of much more of my vocabulary enrichment.