Grandma Bolinger came to our house every few months to spend two weeks with us. She would stay with other relatives too, filling up her years in family guest rooms and bringing to each house her imperious and unbridled judgments on politics, cuisine, television shows, music, and fashion. Admittedly, her taste in clothing was a bit geriatric, but the problem was that she tried to impose that taste upon the rest of the family. Most of her views were set in stone.

One visit began on Halloween night of 1957 when Grandma B arrived wearing an orange cardigan sweater, a black skirt with a large sequined poodle, and saddle shoes with bobby socks, her hair in a long pony tail secured by pink pop-beads. She entered our house with her black handbag and luggage carried by the cab driver, and there was a deafening silence suggesting we were waiting for Grandma to say, “Trick or treat?” The fact is, I would remember that entrance for all Halloweens afterward and recall it later as a “Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?” moment.

We all felt relieved after Grandma confined that long and dangerous hair by the usual bun and doffed those terrifying teenage garments for her usual white blouse, black cardigan, and tweed skirt. Also the comfortable security of her black orthopedic shoes (what my sister Connie Lynn called “Wicked Witch of the West shoes”) brought sighs of relief from the rest of us.

Whenever Grandma B came to our house, we knew that there were certain television programs to be watched at her request. Perry Como made her swoon like the teenager she had appeared to be on Halloween, but his singing was like a powerful sedative to me and my siblings. Grandma, however, was always riveted by his crooning so that no interruptions were looked upon favorably, even coughing, sneezing, or trips to the bathroom. She seemed to have similarly romantic feelings for Lawrence Welk and for James Arness, who played Sheriff Matt Dillon on her other TV addiction, GUNSMOKE. Her final TV requirement was THE JACK BENNY HOUR during which every gesture by Mr. Benny threw the woman into gales of laughter. During these shows my brother David and I would exchange looks of wonder, disgust, and facial contortions suggesting severe stomach cramps.

Even now I blame Lawrence Welk for the next turn of events which began with Myron Floren’s virtuoso accordion performance of “Lady of Spain,” which impressed Grandma B so much that she had to put both hands over her heart. His rendition of “Alice Blue Gown” brought my mother to tears. I was right there in our living room when these performances were watched, but little did I realize the longterm effects of Myron’s fingers flying over those accordion keys.

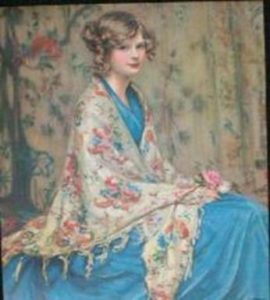

My mother’s attachment to the waltz, “Alice Blue Gown” went back to her first formal dance at the tender age of fifteen, when she had worn a pale blue, floor-length gown and a blue silk ribbon wound through the long braid of hair wrapped around her head. By my father’s account, Mom had been a vision of loveliness and charm that evening with a gorgeous smile and amazing eyes that captivated everyone in the ballroom. As she and my teenaged father entered the room, the orchestra’s conductor turned to see her, abruptly stopped the current musical selection, and played “Alice Blue Gown,” a baritone singing the words, all eyes on my young mother. It was ever afterward my mother’s favorite song.

In her sweet little Alice Blue Gown

When she first wandered down into town,

She was both proud and shy as she felt every eye,

But in every shop window she primped passing by.

In a manner of fashion she found,

and the world seemed to smile all around,

Till it wilted, she wore it.

She’ll always adore it.

Her sweet little Alice Blue Gown.

After dinner one evening Grandma B announced that she thought it time for me to take music lessons and that she would pay for them the first year and even purchase the instrument. The noose was now growing tighter, but I didn’t feel its grip until it was declared that the instrument would be an accordion. The strains of “Lady of Spain” began at that moment to haunt me for the next year. Dad agreed to the proposal and was further moved to acquiesce by the fact that unlike a piano, the accordion was not only portable but would require no rearranging of furniture in our house. Coupled with my parents’ enthusiasm was Grandma B’s irrefutable generosity. It was a done deal. Any hope I had now of escaping those music lessons was like leaving the porch light on for Jimmy Hoffa. I was doomed.

My music lessons began in March of 1958 on a Saturday morning when Miss Clairmont, my instructor, came to our house, where the lessons would be given at the same time each week, ten o’clock sharp for thirty minutes. Miss Clairmont was that day wearing a black pleated skirt, a gray silk blouse, and black beads. Those beads were an omen of things to come, though I hadn’t the sense to be tuned in to anything that morning except Miss Clairmont’s stack of sheet music and rather dazzling accordion, an instrument displaying more mother of pearl and gold leaf than the Palace of Versailles. Her initials, D.A.C., were engraved on a red panel over the keyboard. By contrast my accordion was a sober ebony with no sparkling accoutrements of any kind. The complete appropriateness of that contrast didn’t strike me until much later.

Then I discovered that her name was Diane Arlene Clairmont and that she had actually played the accordion professionally for a couple of years at a night club in Chicago. My first thought on the subject was how terribly far down the woman had fallen. I pictured her once wearing sparkling evening gowns and playing encores of “Lady of Spain” for an intoxicated but affluent audience who would stand and applaud while throwing kisses and ten-dollar bills. Now here she was in our living room of shabby furniture whose glory had also suffered the ravages of time among the cheap art reproductions like our faded prints of “The Laughing Cavalier” by Frans Hals, and “The Blue Boy” by Thomas Gainsborough.

Despite my heart going out to poor Miss Clairmont and my wanting desperately to please her by doing well at my lessons, I was a consummate failure at the accordion, able to play only two songs that people recognized, “Silent Night” and “She’ll Be Comin’ ‘Round the Mountain.” Unless it was the yuletide season, that left only one song to play when visiting relatives asked for a performance. It got run into the ground pretty fast. My rendition of “Alice Blue Gown” turned out to be much bluer than anyone had anticipated, and my chances of ever playing “Lady of Spain” with any competency were as great as my chances of playing “Flight of the Bumble Bee,” starring on the Lawrence Welk Show, or appearing at Carnegie Hall. My mother did cry when I played “Alice Blue Gown,” but I couldn’t tell if her tears were from nostalgia or from the many wrong notes of my less than lovely performances of the song.

The other thing that permanently scarred my ego was that our cocker spaniel, Topper, howled to go outside as soon as I even picked up the accordion, and my family would all leave the house on Saturday mornings at 9:58, always on the pretext of some group errand or on the grounds that they didn’t want to disturb the “flow” of my music lesson. Yeah, right. During the year that I took those lessons, Miss Clairmont never committed suicide, but I imagined more than once her limp body being found in some motel room, her accordion unfolded and sparkling on the bed next to a note explaining her utter revulsion at having to teach music to a boy whose rendition of “Volare” took six weeks for him to learn and another six weeks for her to erase from her memory.

******************************************

This was an excerpt from one of my books…a novel called This Ain’t No Ballet, available as paperback or Kindle on Amazon or as paperback at Barnes & Noble and other bookstores nationwide. JB