We live in a culture that is becoming increasingly politically correct. Everyone seems to have a growing list of things that offend.

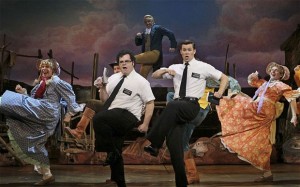

Last night in Denver I saw the Broadway musical, The Book of Mormon. Getting tickets without being a season subscriber was a nightmare, so that when I finally got a ticket, I felt on some level as though I’d won the lottery. Writing any sort of commentary on the show is going to be a true challenge for me, as the story not only lambasts a particular faith (Mormonism), but its irreverent humor in general would offend many friends, who are much more conservative than I. There were times that my subconscious mind felt as though my laughing so hard made me deserve to be excommunicated, even though I’m no longer a member of any church in particular.

Last night in Denver I saw the Broadway musical, The Book of Mormon. Getting tickets without being a season subscriber was a nightmare, so that when I finally got a ticket, I felt on some level as though I’d won the lottery. Writing any sort of commentary on the show is going to be a true challenge for me, as the story not only lambasts a particular faith (Mormonism), but its irreverent humor in general would offend many friends, who are much more conservative than I. There were times that my subconscious mind felt as though my laughing so hard made me deserve to be excommunicated, even though I’m no longer a member of any church in particular.

One would expect the humor of the play to be raw in the sense that it would appall most Sunday school classes in America. The writers also created the animated TV series, South Park, so in that way I was prepared to be shocked by the loose language and constant thwarting of traditional Christian views. Having said that, I can go ahead to say that despite all the religious toes stepped on by the script of the play, I rather enjoyed it. Now let’s see if I can actually defend that view.

One would expect the humor of the play to be raw in the sense that it would appall most Sunday school classes in America. The writers also created the animated TV series, South Park, so in that way I was prepared to be shocked by the loose language and constant thwarting of traditional Christian views. Having said that, I can go ahead to say that despite all the religious toes stepped on by the script of the play, I rather enjoyed it. Now let’s see if I can actually defend that view.

The major thrust of the satire of this play is based upon the premise that Mormons (and indeed many other religious groups) demand acceptance of tenets that defy all logic and human reason, because they seem to be based upon pure fantasy, which has little or nothing to do with the “real” world. This “do what you’re told” mentality can be offensive at times in its intensely synthetic cheerfulness. One of my favorite songs was “Shut It Off,” the lyric of which speaks of not using the brain to reason out the outrageous demands placed upon the believer. This part of organized religion is the main target of the entire musical. Turning off the thinking part of the brain, like turning off a light switch, is basic to Mormonism, among other faiths. Blind acceptance is the core of such religious fervor. The song captures that tendency and mental blindess brilliantly.

The major thrust of the satire of this play is based upon the premise that Mormons (and indeed many other religious groups) demand acceptance of tenets that defy all logic and human reason, because they seem to be based upon pure fantasy, which has little or nothing to do with the “real” world. This “do what you’re told” mentality can be offensive at times in its intensely synthetic cheerfulness. One of my favorite songs was “Shut It Off,” the lyric of which speaks of not using the brain to reason out the outrageous demands placed upon the believer. This part of organized religion is the main target of the entire musical. Turning off the thinking part of the brain, like turning off a light switch, is basic to Mormonism, among other faiths. Blind acceptance is the core of such religious fervor. The song captures that tendency and mental blindess brilliantly.

One of the characters, Elder Cunningham, sent with a group of other elders to Uganda, finds that the dogma of his faith doesn’t work for the natives of that country, so he sets about creating fake dogma of his own, passing it off as Mormon creed. He does this in order to improve the behavior of natives in practical terms. His personal credos are, however, no more ridiculous or outrageous than the Mormon beliefs he was expected to foist off on the people in the first place. Elder Cunningham has to deal constantly with natives asking him, “And how do you know that is true?”

One of the characters, Elder Cunningham, sent with a group of other elders to Uganda, finds that the dogma of his faith doesn’t work for the natives of that country, so he sets about creating fake dogma of his own, passing it off as Mormon creed. He does this in order to improve the behavior of natives in practical terms. His personal credos are, however, no more ridiculous or outrageous than the Mormon beliefs he was expected to foist off on the people in the first place. Elder Cunningham has to deal constantly with natives asking him, “And how do you know that is true?”

Finally, the Mormon head of evangelism arrives in Uganda to check on the elders he has sent there, being appalled at last to see that the residents have been taught everything but Mormon doctrine. He fires all the elders, who decide to stay anyway and to begin their own religion, one that works best to keep the natives happy and civilized. In that way, despite the intervening vulgarity of humor along the way, the ending of the play represents a compassionate turn of events in favor of practicality and loving acceptance of people as they are. In that light, many other organized faiths would probably suffer just as badly as Mormonism. Musically, the evening was very entertaining, especially through the dynamic singing voices of Elder Cunningham, Elder Price, and the Ugandan girl, Nabulungi. All their voices were outstanding and a joy to hear, but don’t expect to be humming any of the tunes as you’re leaving the theater. This isn’t Rodgers and Hammerstein, or Lerner and Lowe. As in most modern musicals, the tunes are forgettable, despite the quality of the singing voices.

Finally, the Mormon head of evangelism arrives in Uganda to check on the elders he has sent there, being appalled at last to see that the residents have been taught everything but Mormon doctrine. He fires all the elders, who decide to stay anyway and to begin their own religion, one that works best to keep the natives happy and civilized. In that way, despite the intervening vulgarity of humor along the way, the ending of the play represents a compassionate turn of events in favor of practicality and loving acceptance of people as they are. In that light, many other organized faiths would probably suffer just as badly as Mormonism. Musically, the evening was very entertaining, especially through the dynamic singing voices of Elder Cunningham, Elder Price, and the Ugandan girl, Nabulungi. All their voices were outstanding and a joy to hear, but don’t expect to be humming any of the tunes as you’re leaving the theater. This isn’t Rodgers and Hammerstein, or Lerner and Lowe. As in most modern musicals, the tunes are forgettable, despite the quality of the singing voices.

Finally, I believe it’s important for those attending the play to go with open minds. Any jabbing at traditional religious icons should be taken with a grain of salt, remembering that the ending of the story is one of compassion, decorated throughout by humor and enjoyable music, and that when the audience leaves, unless they’re Mormons, they feel somewhat better than when they arrived. JB

Finally, I believe it’s important for those attending the play to go with open minds. Any jabbing at traditional religious icons should be taken with a grain of salt, remembering that the ending of the story is one of compassion, decorated throughout by humor and enjoyable music, and that when the audience leaves, unless they’re Mormons, they feel somewhat better than when they arrived. JB