This is an excerpt from my third book, COME SEPTEMBER, Journey of a High School Teacher (available as Kindle or paperback on Amazon.com). The experiences described in this piece show the importance of considering one’s career choices carefully.

**************************************

One annoyance that at the time can seem unbearable, but that later on can become a blessing, is having a job when you’re young that you truly hate, even if just for a little while. That detested employment can make one appreciate his true calling even more when it comes along, and can inspire anyone to keep looking for that occupational niche that fits him or her best, simply by making him want to escape whatever job is dull, meaningless, laborious, or just tedious.

My very worst days in teaching were all far better than even my best days at Inland Steel in Gary, Indiana. The summer of 1968 I worked on the Cold Strip Number Three in Gary for a couple of months, but my time on that job would forever after make me grateful that it had not become my life’s work. Being there even for that short time helped me to comprehend and esteem the profession of teaching high school.

My very worst days in teaching were all far better than even my best days at Inland Steel in Gary, Indiana. The summer of 1968 I worked on the Cold Strip Number Three in Gary for a couple of months, but my time on that job would forever after make me grateful that it had not become my life’s work. Being there even for that short time helped me to comprehend and esteem the profession of teaching high school.

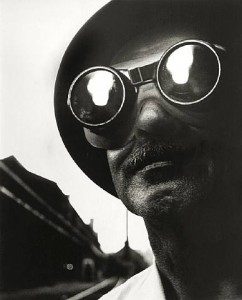

My most representative recollection of that summer at Inland was the first day, when I was an obvious green horn, wearing my brand new stiff, heavy work boots, clothes, and hard hat. Add to those the bug-eyed goggles, and you’ve conjured up the picture of a deep-sea diver. Our foreman, Joe Flint, was a sadistic, beer-bellied brute, about forty years old, who seemed to enjoy making everyone around him as uncomfortable as he could. He loved showing off his authority in ways that would embarrass anyone over whom he thought he had power. The fact that he never uttered a sentence without a double negative and at least three curse words made him less colorful than just plain mean and hopelessly stupid. One of those people who enjoyed looking down on others, Flint was also an open racist and made himself feel superior at the expense of those round him. Their pain and humiliation seemed to lift his spirit (if he had one).

My most representative recollection of that summer at Inland was the first day, when I was an obvious green horn, wearing my brand new stiff, heavy work boots, clothes, and hard hat. Add to those the bug-eyed goggles, and you’ve conjured up the picture of a deep-sea diver. Our foreman, Joe Flint, was a sadistic, beer-bellied brute, about forty years old, who seemed to enjoy making everyone around him as uncomfortable as he could. He loved showing off his authority in ways that would embarrass anyone over whom he thought he had power. The fact that he never uttered a sentence without a double negative and at least three curse words made him less colorful than just plain mean and hopelessly stupid. One of those people who enjoyed looking down on others, Flint was also an open racist and made himself feel superior at the expense of those round him. Their pain and humiliation seemed to lift his spirit (if he had one).

The first day, Flint announced that he needed the college students for a special job. Sam, Frank, and I stepped forward to be informed by the smirking Flint that we would be spending the day cleaning dead rats, and maybe a few live ones, out of the grease pits. I’ll never forget the three of us up to our ankles in oil and grease, shoveling dead rats, Flint looking down on us from above, laughing as we three slipped around the pit, wiping our sweaty brows with our greasy gloves and sleeves.

The first day, Flint announced that he needed the college students for a special job. Sam, Frank, and I stepped forward to be informed by the smirking Flint that we would be spending the day cleaning dead rats, and maybe a few live ones, out of the grease pits. I’ll never forget the three of us up to our ankles in oil and grease, shoveling dead rats, Flint looking down on us from above, laughing as we three slipped around the pit, wiping our sweaty brows with our greasy gloves and sleeves.

It became increasingly clear over the summer how much Flint hated us, despite our humility and obedience. Perhaps all of his animosity was based upon the fact that he was keenly aware of our temporary presence there, and that we three would be moving on to other jobs, where we could find a sense of fulfillment and happiness that Flint had never found and probably never would. There was, according to Frank, a terrible jealousy in Flint’s nature that always surfaced whenever any of us three college students, whom Flint called “college stooges,” did something right, which admittedly wasn’t all that often. Those times he would simply scoff at us, never encouraging us in any way that we were on the right track. When, however, we did something wrong, he would laugh gleefully, as when Sam slipped on a patch of grease and badly cut his left arm on the razor edges of a giant steel coil one morning and was rushed to the infirmary, where he had thirty-seven stitches. Afterward, Flint laughed himself breathless in repeating the story of the “dumb-ass college twerp” to anyone who would listen.

It became increasingly clear over the summer how much Flint hated us, despite our humility and obedience. Perhaps all of his animosity was based upon the fact that he was keenly aware of our temporary presence there, and that we three would be moving on to other jobs, where we could find a sense of fulfillment and happiness that Flint had never found and probably never would. There was, according to Frank, a terrible jealousy in Flint’s nature that always surfaced whenever any of us three college students, whom Flint called “college stooges,” did something right, which admittedly wasn’t all that often. Those times he would simply scoff at us, never encouraging us in any way that we were on the right track. When, however, we did something wrong, he would laugh gleefully, as when Sam slipped on a patch of grease and badly cut his left arm on the razor edges of a giant steel coil one morning and was rushed to the infirmary, where he had thirty-seven stitches. Afterward, Flint laughed himself breathless in repeating the story of the “dumb-ass college twerp” to anyone who would listen.

My contempt for Flint was always clear to me, but my pity for him didn’t materialize until near the end of the summer, when I began to find that everyone else at the plant hated him too, even more than we three lowly students did. He was reviled by everyone else but continued to believe that his cruel and contemptible behavior was somehow humorous, entertaining, and admired. I found this rather sad, but at the end of the summer, Frank, Sam, and I joyfully left Inland Steel, none of us saying goodbye to Flint, who had never offered even one word of hope or kindness to any of us. As our bus pulled away from the plant, and Cold Strip #3 grew smaller behind us, I pictured Flint remaining a wretched and empty man into old age, vilified by all who knew him. That thought softened the disgust and loathing that I needed to leave behind.

My contempt for Flint was always clear to me, but my pity for him didn’t materialize until near the end of the summer, when I began to find that everyone else at the plant hated him too, even more than we three lowly students did. He was reviled by everyone else but continued to believe that his cruel and contemptible behavior was somehow humorous, entertaining, and admired. I found this rather sad, but at the end of the summer, Frank, Sam, and I joyfully left Inland Steel, none of us saying goodbye to Flint, who had never offered even one word of hope or kindness to any of us. As our bus pulled away from the plant, and Cold Strip #3 grew smaller behind us, I pictured Flint remaining a wretched and empty man into old age, vilified by all who knew him. That thought softened the disgust and loathing that I needed to leave behind.

Despite the awful experiences of that summer, I had learned at least one valuable lesson, that whatever authority I was to be given as a school teacher, I would never use it to scorn, embarrass, or hurt anyone. Flint would remain the standard for everything I abhorred about our weaknesses as a species. Whenever I felt myself becoming the least bit mean-spirited, cruel, overbearing, or arrogant, I would remember Joe Flint and be instantly horrified by the mere possibility of being anything like him. In that respect, maybe Frank, Sam, and I, along with countless others, owe Flint our gratitude for helping to make us all, even if unintentionally, better people. Flint would remain forever our most vivid model of what not to become as human beings.

Despite the awful experiences of that summer, I had learned at least one valuable lesson, that whatever authority I was to be given as a school teacher, I would never use it to scorn, embarrass, or hurt anyone. Flint would remain the standard for everything I abhorred about our weaknesses as a species. Whenever I felt myself becoming the least bit mean-spirited, cruel, overbearing, or arrogant, I would remember Joe Flint and be instantly horrified by the mere possibility of being anything like him. In that respect, maybe Frank, Sam, and I, along with countless others, owe Flint our gratitude for helping to make us all, even if unintentionally, better people. Flint would remain forever our most vivid model of what not to become as human beings.

The painful experiences we have, especially when we’re young, can scar us, harden us, or give us a different kind of understanding and strength to face other things later on. Each one of us can probably think of a nemesis from his or her past, someone who seemed to enjoy making us miserable, but who could also make us appreciate others in our lives who had inspired us with their kindness or encouragement. The unhappy jobs we endured as stock boys in grocery stores serving thoughtless and rude customers, laborers in hot, uncomfortable factories, newspaper delivery boys, baby sitters for monster kids, or work at any other jobs we found to be all but unbearable, serve to give us the desire to do something else, something with creative satisfaction and meaning that goes right to the core of who we are and who we want to become. That need to look “elsewhere” stops perhaps when we discover our callings, that overwhelming and all consuming realization that in our work, we’re doing what we were meant to do as our principal occupation or career in life. As a kid I had enjoyed playing school and pretending to be a teacher or principal, so the desire had always been there, but there are probably many who stumble upon their choices for work much later and by pure accident, but that doesn’t diminish the power of finding one’s own calling, whenever it happens.

The painful experiences we have, especially when we’re young, can scar us, harden us, or give us a different kind of understanding and strength to face other things later on. Each one of us can probably think of a nemesis from his or her past, someone who seemed to enjoy making us miserable, but who could also make us appreciate others in our lives who had inspired us with their kindness or encouragement. The unhappy jobs we endured as stock boys in grocery stores serving thoughtless and rude customers, laborers in hot, uncomfortable factories, newspaper delivery boys, baby sitters for monster kids, or work at any other jobs we found to be all but unbearable, serve to give us the desire to do something else, something with creative satisfaction and meaning that goes right to the core of who we are and who we want to become. That need to look “elsewhere” stops perhaps when we discover our callings, that overwhelming and all consuming realization that in our work, we’re doing what we were meant to do as our principal occupation or career in life. As a kid I had enjoyed playing school and pretending to be a teacher or principal, so the desire had always been there, but there are probably many who stumble upon their choices for work much later and by pure accident, but that doesn’t diminish the power of finding one’s own calling, whenever it happens.

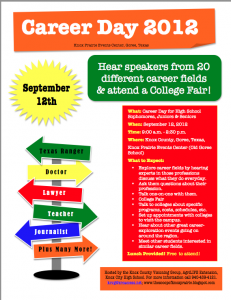

Some kids know as early as middle school what their callings are. Others don’t know until after high school, and still others never really know what they were meant to do, which is why I believe strongly in high schools having “career” days, where many choices are presented interestingly with large amounts of information and the chance for kids to ask questions. Options are needed so they can be matched with preferences and inclinations that may otherwise remain untapped or unrecognized, allowing some students to drift aimlessly toward conveyor belt jobs, where those people may or may not find their callings but stay just to get by. That isn’t to say that kids are mere fodder for the work place, though it often seems that way, but finding what they like and do best seems vastly important to individuals and to society. Not everyone has to attend college, but the essential thing is to help kids know what’s out there for them in the way of employment in which they can find some measure of significance, security, and pride. JB

Some kids know as early as middle school what their callings are. Others don’t know until after high school, and still others never really know what they were meant to do, which is why I believe strongly in high schools having “career” days, where many choices are presented interestingly with large amounts of information and the chance for kids to ask questions. Options are needed so they can be matched with preferences and inclinations that may otherwise remain untapped or unrecognized, allowing some students to drift aimlessly toward conveyor belt jobs, where those people may or may not find their callings but stay just to get by. That isn’t to say that kids are mere fodder for the work place, though it often seems that way, but finding what they like and do best seems vastly important to individuals and to society. Not everyone has to attend college, but the essential thing is to help kids know what’s out there for them in the way of employment in which they can find some measure of significance, security, and pride. JB