My dad was a drinker. I don’t mean that he was a social drinker, someone who has cocktails at seven just before dinner, one of those special Christmas punch, occasional imbibers, or a man who enjoys Friday evening, slap-on-the-back beers with the guys down at the Shamrock Tap. No, I mean that he was a studied, rye whiskey, Chivas Regal, Bombay Sapphire Dry Gin, hidden-behind-wall-panels consumer of alcohol in magnum proportions, and for whom every hour was an occasion to celebrate even life’s tiniest victories, or to soothe its many wounds, real or imagined. His thirst was unending, because his search for that equilibrium of mind we call peace remained unquenchable. I’m not sure if our family has a crest or coat of arms, but if we do, I imagine it to be a bottle of Johnny Walker on top of a hospital gurney, both entwined by a tasteful swirl of poison ivy.

The level of codependency between my parents was of such extraordinary color and depth, that any expert on psychology would have given anything to study it before turning it into an award-winning, best-selling book and then receiving big money for rights to a Hollywood movie version starring Tommy Lee Jones and Susan Sarandon. Mom was a martyr whose closed eyes and flared nostrils were most often evident during or after Dad’s many drinking episodes, which on occasion would become binges over a weekend or even the better part of a month, after which Dad would appear suddenly at dinner, suitcase in-hand, wearing a deceptively cheerful smile suggesting that no one would be so crass as to pose any questions about his whereabouts over the previous days or weeks. He would then attempt to buy us off with presents from wherever he had been. Over the years I accumulated a stash of records, leather belts, pen knives, sweaters, and mechanical pencils with my initials engraved in gold, all from places everywhere from Tacoma to Baltimore. My sister Connie usually got dolls, Mom would get jewelry, and my brother David the plastic shrunken heads he needed for his vast and grisly collection.

The level of codependency between my parents was of such extraordinary color and depth, that any expert on psychology would have given anything to study it before turning it into an award-winning, best-selling book and then receiving big money for rights to a Hollywood movie version starring Tommy Lee Jones and Susan Sarandon. Mom was a martyr whose closed eyes and flared nostrils were most often evident during or after Dad’s many drinking episodes, which on occasion would become binges over a weekend or even the better part of a month, after which Dad would appear suddenly at dinner, suitcase in-hand, wearing a deceptively cheerful smile suggesting that no one would be so crass as to pose any questions about his whereabouts over the previous days or weeks. He would then attempt to buy us off with presents from wherever he had been. Over the years I accumulated a stash of records, leather belts, pen knives, sweaters, and mechanical pencils with my initials engraved in gold, all from places everywhere from Tacoma to Baltimore. My sister Connie usually got dolls, Mom would get jewelry, and my brother David the plastic shrunken heads he needed for his vast and grisly collection.

While Dad was away on one of his jaunts, newspaper headlines like, “Drunk Man Climbs High Voltage Wires” would haunt us at home, because we were all familiar with the Twilight Zone world Dad inhabited while he was drinking. Nothing phased him, and he knew no fear or sense of decorum when he was looped. Once home, Dad would ease back into his habit of eating his dinner from a TV tray in the living room while watching Hogan’s Heroes and Family Feud, as the rest of us listened from the dining room to his hearty laughter and trumpeting farts through paisley boxer shorts, his favorite attire for the dinner hour.

While Dad was away on one of his jaunts, newspaper headlines like, “Drunk Man Climbs High Voltage Wires” would haunt us at home, because we were all familiar with the Twilight Zone world Dad inhabited while he was drinking. Nothing phased him, and he knew no fear or sense of decorum when he was looped. Once home, Dad would ease back into his habit of eating his dinner from a TV tray in the living room while watching Hogan’s Heroes and Family Feud, as the rest of us listened from the dining room to his hearty laughter and trumpeting farts through paisley boxer shorts, his favorite attire for the dinner hour.

Sometimes Dad would have dry heaves at night or react irrationally to something, as in his getting up at four in the morning to shoot his pistol at the chimney, where he claimed a crow that sounded like Phyllis Diller was laughing at him. Or, he’d wander downstairs in his boxers during other wee hours to sit with some cheddar cheese and a bottle of port in front of the TV to watch infomercials and programs like Bowling for Dollars until dawn.

Sometimes Dad would have dry heaves at night or react irrationally to something, as in his getting up at four in the morning to shoot his pistol at the chimney, where he claimed a crow that sounded like Phyllis Diller was laughing at him. Or, he’d wander downstairs in his boxers during other wee hours to sit with some cheddar cheese and a bottle of port in front of the TV to watch infomercials and programs like Bowling for Dollars until dawn.

Mom’s release valve came in talking daily on the phone to our Aunt Florence to relate my father’s most recent, grotesque encounters with his inner world through liquor. The most amazing thing about those years was the miracle that Dad never lost his job, which made me think his employers at Krall Electric were either extremely liberal or unbelievably unobservant. At any rate, Aunt Flo’s shrill voice could always be heard piercing the air from our phone, even from the next room, saying, “Fer Chrissake! Is that a fact? Did he really? You don’t mean it!” She provided Mom with a soundboard off which to bounce her dreary life of laundry, cooking, cleaning, and creating stories to cover the fact that Dad was an inebriate of colossal proportions. Lies flew around like a plague of locusts so that people wouldn’t drop by to visit our home. At one time or another, we all had brain tumors, asthma, and a host of communicable diseases to ward off any possible guests. I remember Mom telling Judd, my brother’s best friend, that David was just getting over rickets and couldn’t have company yet.

Mom’s release valve came in talking daily on the phone to our Aunt Florence to relate my father’s most recent, grotesque encounters with his inner world through liquor. The most amazing thing about those years was the miracle that Dad never lost his job, which made me think his employers at Krall Electric were either extremely liberal or unbelievably unobservant. At any rate, Aunt Flo’s shrill voice could always be heard piercing the air from our phone, even from the next room, saying, “Fer Chrissake! Is that a fact? Did he really? You don’t mean it!” She provided Mom with a soundboard off which to bounce her dreary life of laundry, cooking, cleaning, and creating stories to cover the fact that Dad was an inebriate of colossal proportions. Lies flew around like a plague of locusts so that people wouldn’t drop by to visit our home. At one time or another, we all had brain tumors, asthma, and a host of communicable diseases to ward off any possible guests. I remember Mom telling Judd, my brother’s best friend, that David was just getting over rickets and couldn’t have company yet.

This was the worst part of having an alcoholic father. Lying required too much collective energy to keep it a secret. Having our friends over was a tricky business in the sense that it was almost impossible to plan visits around my father’s unpredictable drinking fests, and it was too terrifying to imagine a friend coming over for an algebra study session that might end with my dad stumbling into the room wearing his boxer shorts and farting like a bilge pump, followed by his dissertation on how Eskimos were really onto something in their practice of putting their elderly onto ice floes and sending them out permanently to sea. His slurred speech was a huge signal that he was “shnockered,” and it would take only one loose-tongued, even if well-meaning buddy to have the story in every house in town by the next morning.

This was the worst part of having an alcoholic father. Lying required too much collective energy to keep it a secret. Having our friends over was a tricky business in the sense that it was almost impossible to plan visits around my father’s unpredictable drinking fests, and it was too terrifying to imagine a friend coming over for an algebra study session that might end with my dad stumbling into the room wearing his boxer shorts and farting like a bilge pump, followed by his dissertation on how Eskimos were really onto something in their practice of putting their elderly onto ice floes and sending them out permanently to sea. His slurred speech was a huge signal that he was “shnockered,” and it would take only one loose-tongued, even if well-meaning buddy to have the story in every house in town by the next morning.

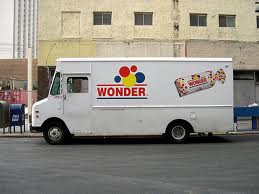

Dad didn’t join Alcoholics Anonymous until after the night during the time I was a senior in high school, when we received a phone call from the police telling us that Dad had been in an auto accident, and that Sergeant Murphy would be bringing him home in a squad car. Of course, that flashing red light in our neighborhood at ten in the evening was probably a catalyst for the story being slapped into a nationwide hookup within hours. It seems that Dad had sideswiped a Wonder Bread delivery truck, finally mashing the truck’s back end message of HELPS YOUR BODY GROW TWELVE WAYS into the colorfully ballooned, accordion-pleated, remaining letters, HELPS YOUR BODY GROW ELVES.

Dad didn’t join Alcoholics Anonymous until after the night during the time I was a senior in high school, when we received a phone call from the police telling us that Dad had been in an auto accident, and that Sergeant Murphy would be bringing him home in a squad car. Of course, that flashing red light in our neighborhood at ten in the evening was probably a catalyst for the story being slapped into a nationwide hookup within hours. It seems that Dad had sideswiped a Wonder Bread delivery truck, finally mashing the truck’s back end message of HELPS YOUR BODY GROW TWELVE WAYS into the colorfully ballooned, accordion-pleated, remaining letters, HELPS YOUR BODY GROW ELVES.

After that night, I began to wonder if we were the only family in town with a tipsy father. I looked above my bed at the shelves filled with gifts that had been my dad’s bribes not to stand up to him about his drinking. The gifts all looked like those boxes of chocolates that lie on drugstore shelves with expiration dates from when some of us were toddlers, and I resolved not to ignore the problem anymore, but to talk about it during whatever lucid moments Dad was willing to share. As it turned out, we weren’t alone. Any number of kids at school had parents whose drinking was out of control. There was a community of people I could actually talk to with problems we could carry collectively on more than a couple of shoulders. None of this, however, had any effect on my dad’s penchant for boxer shorts, his farting, or my brother’s obsession with shrunken heads, but life did improve for my family over time. JB

After that night, I began to wonder if we were the only family in town with a tipsy father. I looked above my bed at the shelves filled with gifts that had been my dad’s bribes not to stand up to him about his drinking. The gifts all looked like those boxes of chocolates that lie on drugstore shelves with expiration dates from when some of us were toddlers, and I resolved not to ignore the problem anymore, but to talk about it during whatever lucid moments Dad was willing to share. As it turned out, we weren’t alone. Any number of kids at school had parents whose drinking was out of control. There was a community of people I could actually talk to with problems we could carry collectively on more than a couple of shoulders. None of this, however, had any effect on my dad’s penchant for boxer shorts, his farting, or my brother’s obsession with shrunken heads, but life did improve for my family over time. JB